Healthy landscapes are naturally full of good food. Taking an interest in the open spaces around you can be a way to put money in the piggy bank for later. People and cultures around the world historically took care of their ecosystems almost like elaborate gardens, making sure there was lots of food for their community, and also space for other living things to thrive.

Unfortunately most people now live very disconnected from the living world. They don’t have names for the plants they see, and have no idea what the landscape should look like in their region. Those in cities are doubly removed because they assume the natural world doesn’t coexist when pavement is around.

Learning the plants that produce food in your region enables you to improve your community food security even without garden space of your own. In this section we will focus on native plants in order to ensure that the ecology is also supported in the process.

Food Systems

Most people familiar with farming and gardening think about a single type of landscape. Garden soil (dark, moist, crumbly) spread in an open area in full sun, plants spaced apart, and every year the plants dying back in fall or winter.

But there are a range of landscape types all over the world, and almost every one of them produces food. As you’ll see in a moment some ecosystems can sustain more humans than others. Regardless of the type, they can be encouraged to produce more food – and this process often improves their ecological health as well.

When looking for landscapes around you to work as a food system, it’s best to look for landscapes that are:

- Abundant – large areas are best.

- Without care – If a lot of people already have an interest in the area, they may already be caring for the ecosystem to suit their needs and harvests.

- Fewest Limiting Factors – The most moist, sunny, fertile areas, will generally produce the most food.

Limiting Factors

Plants are machines that turn light into living material (including food like fruits and vegetables). For the purposes of this topic, we can imagine plants like a mathematical equation:

| Sunlight + Water + Soil Nutrients + Other Stuff -> Plant Material + Other Stuff |

This means that areas with a lot of light, moisture, and nutritious soils, will usually produce the most amount of food. The more you restrict these (like very shady areas, very dry areas, or very low soil-nutrient areas) the more you have limits on plant growth.

Generally speaking the factor you have in the lowest amounts will be the ‘limiting factor’ – or the thing that decides how much a plant grows. That means if you add fertilizer or sun to dry soil, you’ll notice no improved growth. Fixing the limiting factor is what allows the plant to grow bigger and faster.

Some plants have figured out ways to bypass or adapt to their system’s limiting factors – for example, cacti store water, plants like the venus fly trap eat insects for nutrients – but as a general rule these are still lower-productivity systems, because these adaptations still take time and energy to produce. It’s worth remembering though that even low-production systems are incredible hotbeds of biodiversity and can be the easiest systems to grow in certain regions. Trying to figure out how to get water into the desert is a lot harder than figuring out how to grow cactus fruit.

However, for many systems the limiting factors have been historically managed to encourage plant growth. The methods of ecological care typically included flooding / water management, fires, cutting down trees, and the herding and hunting of animals. Learning the traditional management methods of your region can provide clues on how to reduce the limiting factors such that more food and biodiversity is possible.

Major Food Systems

Not that this guide is focused on the mid atlantic, but this could apply to other regions as well.

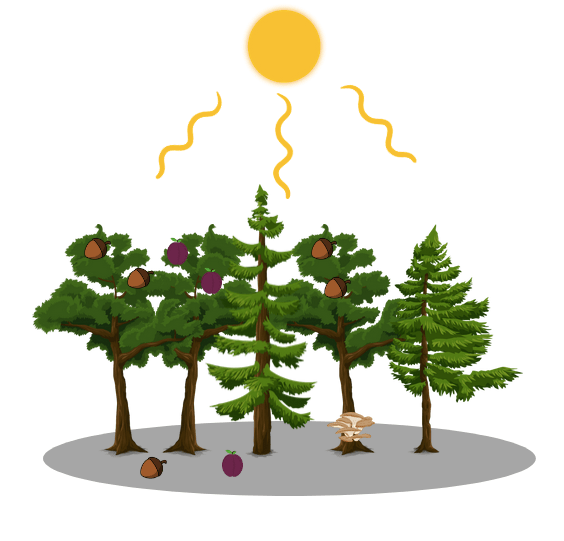

- Shaded Forests – Woods where the ground is dark from lots of trees close together.

- Open Forests – Open woods with lots of sunlight on the ground between the trees.

- Prairies – Landscapes that are almost entirely grasses, flowers, and shrubs, mostly without trees.

- Coasts – Sometimes marshy estuaries, sometimes sandy dunes, usually salt-heavy from sea spray.

- Wetlands – Swamps, rivers, lakes, coasts, etc. Full of water some or all of the year.

Shaded Forests

Major food systems:

- Syrup from trees (primarily maple)

- Nuts on ground from tall trees

- Fruit on ground from tall trees

- Mushrooms

Shaded forests are limited by the amount of sunlight reaching plants. Only the tall trees who have reached the very top of the woods (the canopy) have enough sun to produce food. Typically the trees are kept very skinny because they are bordered on all sides by other trees competing for sunlight – like a person in a dense crowd who can’t reach their arms out without hitting someone else. There is no light on the ground for shrubs or other plants to grow.

This darkness keeps the area more wet and cool, which is called ‘mesic’ in scientific terms. Mesic forests often have a lot of maples and other trees which can be tapped for syrup. The damp cool dark soil also makes excellent conditions for mushrooms to grow, including many edible species.

Trying to get food from these forests is tricky. Trees are one of the few species in this landscape type which produces human food, and they’re very limited due to crowding and low sunlight. Adding more food plants is not a great option in shaded forests because they can’t reach the canopy and be productive in a typical human lifetime. There are a few species of tuberous plants that can be introduced, but these aren’t super nutritious and don’t grow fast. But they’re really valuable to the ecosystem, and a few specialty nurseries have begun propagating and making them available online.

This all means that shaded forests have a limited set of possibilities. Either they can be transitioned to an open forest, or they can be managed and harvested in a more passive way – basically taking the leftovers from an already lower-producing system.

Under the landscape management of the Haudenosaunee (known to many people by the name given by Europeans – the Iroquois), closed woods were historically not the primary sources of food – those were hunting / fishing, cleared land for agriculture, and orchards, though maple syrup was a staple food. To this day some members of the Haudenosaunee Nations have maple forests managed for syrup which is available for purchase online.

Useful Skills:

- Syrup tapping – Syrups are a traditional food harvested in mesic forests, and can provide a lot of calories.

- Tree thinning – Increasing sunlight by removing some trees will improve the amount of food produced. This may begin to transition a closed forest into an open forest.

- Invasive species removal – Invasive vines and shrubs are a major threat to the productivity of these systems, removing them ensures food production continues.

- Deer management – Much of eastern North America has deer overpopulation issues. Encouraging hunting, and fencing young plants, helps to make sure the forest continues to grow.

- Mushroom cultivation – you can encourage mushrooms to grow by taking newly dead trees, and seeding them with culinary mushrooms.

High-Macronutrient Foods to Identify:

- Nuts – Acorns+, Hickory Nuts+, Beech Nuts, Walnuts+, Butternuts+, Chestnuts*+(native is very rare)

- Fruits – Cherry%, Persimmon+, Paw paw

- Mushrooms – Culinary varieties including Puffball, Oyster, Chicken & Hen of The Woods, and Morels

Low-productivity plants to maybe add:

- Tubers – Spring beauty- (claytonia), Ground bean- (Amphicarpaea bracteata), Ramps- (Allium tricoccum)

- Fruit – Pawpaw- (Asimina triloba)

Key: + great producer, ++ excellent producer, -minimally productive, ^ semi-domesticated or quasi-native, * Non native, %caution – needs processing / toxic compounds / dangerous lookalikes / common intolerances / not studied for safety, ! aggressive

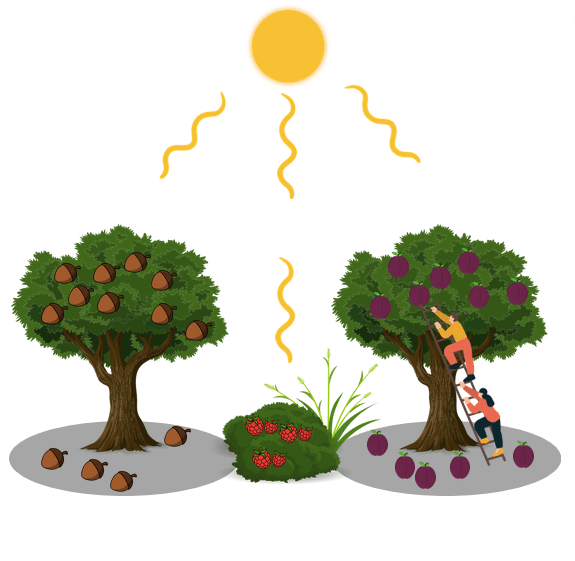

Open Forests

Major food systems:

- Nuts from trees & shrubs

- Fruit from many sources

- Tubers & Seeds growing in sun between trees

Open forests were much more common prior to European contact with the North American continent. These woodlands are often managed with fire or selective cutting down of trees. Buffalo also kept these woods open through grazing and killing trees, and their range used to go from eastern California to western New York.

By allowing each tree to grow as large as possible without getting crowded, it gets the maximum amount of sunlight possible – and thus produces the maximum amount of food. Notably the spacing also discourages squirrels from stealing all the food (they get nervous because is no escape route to other trees if a hawk visits). Lower branches which are squeezed out in tighter closed forests, are often fully developed in open conditions and may be reachable with a ladder.

In the space between the trees where light hits the ground, shrubs, grasses, and flowers have room to flourish. These support unique species, and also can provide additional sources of human food.

Useful Skills:

- Invasive species removal – Invasive vines and shrubs are a major threat to the productivity of these systems, removing them ensures food production continues.

- Pruning – Keeping trees properly shaped helps them stay healthy and productive for longer

- Deer management – Much of eastern North America has deer overpopulation issues. Encouraging hunting, and fencing young plants, helps to make sure the forest continues to grow.

- Controlled burns or seasonal mowing – keeping open forests open requires care and attention. In some places this is done with controlled burns. In areas where burns are restricted, mowing at specific times of the year kills tree seedlings that would begin to close the forest and shade everything out.

- Grazing animals– For those who have access to grazing animals, moving them occasionally through these woods will keep them open and can replace mowing. Common grazing animals include sheep, cows, horses, llamas and geese.

- Plant cultivation – Acquiring seeds, roots, and cuttings, and preparing them to be introduced into the landscape.

Tall trees to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Oak+, Hickory+, Walnut/Butternut+, Beech

- Fruit – American Persimmon+

Small trees to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Chestnut*+

- Fruit – Hackberry, Apple*++ / Crabapple+ (Malus), Plum*+, wild plum+ / wild cherry% (prunus)

Shrubs to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Hazelnut+

- Fruit – Raspberries / Blackberries (Rubus), Blueberry / Deerberry / Huckleberry (Vaccinium), Figs*

Vines to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios americana)++!%

- Fruit – Passionflower!

- Seeds – Wild Beans%- (Phaseolus, Amphicarpaea), Goosefoot / wild Quinoa^ (Chenopodium)

Herbs (non-woody plants) to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Camas+%, Sunchoke^++%,

- Seeds – Sunflower^++,

- Fruit – Pumpkin^++

Key: + great producer, ++ excellent producer, -minimally productive, ^ semi-domesticated or quasi-native, * Non native, %caution – needs processing / toxic compounds / dangerous lookalikes / common intolerances / not studied for safety, ! aggressive

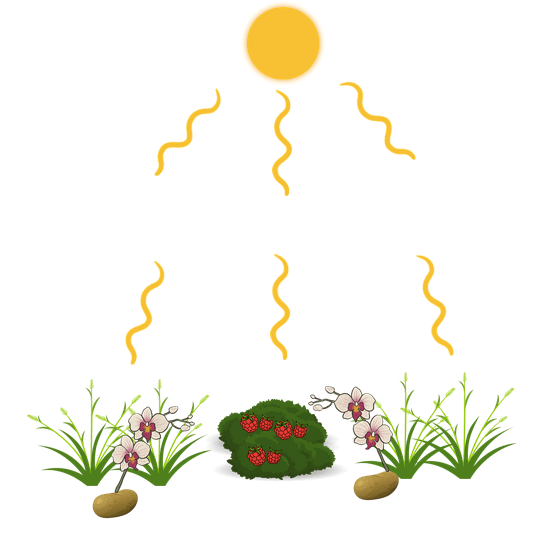

Prairies

Major food systems:

- Fruits & nuts from shrubs

- Tubers and roots

- Various seeds

Prairie ecosystems have the maximum amount of light hitting the ground, but lose the potential productivity of trees. People who lived in these open spaces generally relied on tuberous plants and hunted meat to get through the year. Like open woods, this ecosystem was maintained through a combination of burning and buffalo grazing, with herds moving across the continent.

The Lakota peoples (among many other nations like the Dakota and Nakota) harvested the Timpsila tuber for generations. Unfortunately the range of the tuber has decreased dramatically in the post-colonization landscape under European-style land management. But many nation keep the traditions alive to this day and are actively protecting and growing the range. The sites of tuber growth can be closely guarded, and people who approach this plant should do so with respect. Similarly camas tubers have been a valued food for peoples across the continent in managed floodplains and other open areas. Numerous other thick-rooted plants can be found almost everywhere.

Grasses and shrubs also provide some calories in the form of nuts and seeds. Historically these were minimally productive, but people have spent thousands of years developing and improving these wild plants. For example, the Sunflower likely originated as a weedy plant growing in openings made by buffalo in the plains – people began selecting for greater and greater seed size and eventually developed the plant we know today. Prior to the introduction of corn, plants domesticated from buffalo wallows were a major agriculture plant. Even the non-domesticated grasses still produce seeds that provide a minor food source.

Some accounts say that a traveler could cross enormous distances relying entirely on the foods already planted in the landscape, though in return they were responsible for managing these areas for the next visitor – by returning some seeds or roots, or otherwise caring for the landscape. The current non-Indigenous North American land management systems has allowed these areas to degrade so much, it’s almost impossible to imagine such luxuries. But we can begin to rebuild and make these open landscapes resilient again.

The key to operating these prairie spaces is to make sure that they’re rigorously mown, burned, or grazed, and the density of plants carefully managed. Typically this means a heavy mow or burn somewhere between once every five years, up to twice a year in some circumstances. Thickets can be encouraged by leaving certain areas unmown for longer time periods which enables tangled shrubs to form – these are home for wildlife and can be great sources of food. Intentionally planting human food has likely been the norm for millennia, though with plenty of space for other plants and animal habitat as well. This means that weaving in planting, harvesting, and weeding, into the management plant is an excellent way to keep food production high in a sustainable manner.

Useful Skills:

- Invasive species removal – Invasive vines and shrubs are a major threat to the productivity of these systems, removing them ensures food production continues.

- Deer management – Much of eastern North America has deer overpopulation issues. Encouraging hunting, and fencing young plants, helps to make sure the forest continues to grow.

- Controlled burns or seasonal mowing – keeping open forests open requires care and attention. In some places this is done with controlled burns. In areas where burns are restricted, mowing at specific times of the year kills tree seedlings that would begin to close the forest and shade everything out.

- Grazing animals– For those who have access to grazing animals, moving them across the land can replace mowing. Common grazing animals include sheep, cows, horses, llamas and geese.

- Plant cultivation – Acquiring seeds, roots, and cuttings, and preparing them to be introduced into the landscape.

Shrubs & Thickets to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Hazelnut+

- Fruit shrubs – Raspberries / Blackberries (Rubus), Blueberry / Deerberry / Huckleberry (Vaccinium), Figs*+

- Fruit thickets – Plums+(Prunus), American Persimmon+ (Diospyros virginiana), Serviceberry (Amelanchier)

Vines to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios americana)++!%

- Fruit – Passionflower!

- Seeds – Wild Beans- (Phaseolus)%

Herbs (non-woody plants) to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Camas+% , Sunchoke^++!%,

- Seeds – Sunflower^++, Goosefoot / wild Quinoa^ (Chenopodium), Evening primrose!% (Oenothera biennis)

- Fruit – Pumpkin^++

Key: + great producer, ++ excellent producer, -minimally productive, ^ semi-domesticated or quasi-native, * Non native, %caution – needs processing / toxic compounds / dangerous lookalikes / common intolerances / not studied for safety, ! aggressive

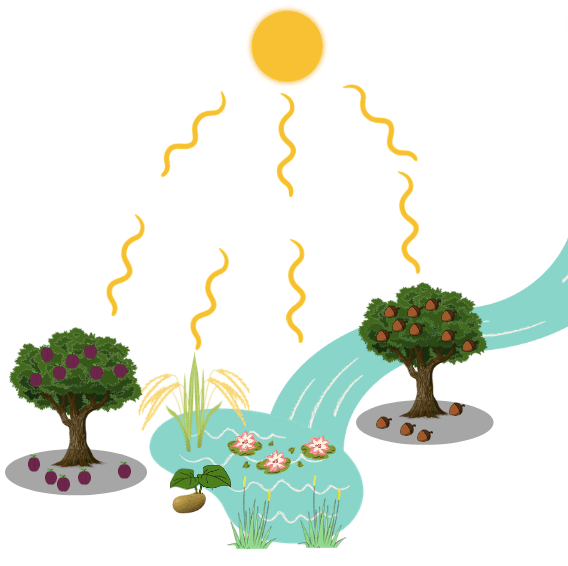

Wetlands

Major food systems:

- Fruits from shrubs & trees

- Nuts from shrubs & trees

- Tubers and Roots

- Various seeds

Wetlands are one of the most helpful and productive ecosystems, and the least well understood by regular people. Historically these landscapes had incredible food and fiber production for people around the world. They also provided lots of bonus services – regulating temperature, cleaning water, and slowly producing raw iron that could be used to make tools and weapons. Today they’re also one of the best storage systems for carbon, and so help us to fight climate change.

Scientists consider an area a wetland if it has 3 special characteristics:

- Soil that’s had water in it long enough to experience specific changes (known as hydric soils)

- Plants that are adapted to grow in wetlands (known as hydrophytes)

- Signs of water (this may be above or below the soil, sometimes not obvious outside of mucky flooding seasons)

The limiting factors that hold back other ecosystems – sunlight, water, nutrition – are usually bountiful in wetlands. Instead plants struggle against low oxygen from being underwater, and must survive their soil being disturbed by rainstorms and floods. Some higher areas may stay drier and support tree or shrubs.

Species planted in wetlands for food can’t be dry-only species – they will drown in the moisture. Luckily wetland scientists have classified plants into 5 categories that describe their ability to survive in wetland or upland conditions:

- Obligate (OBL) – can only survive in wet or aquatic areas (meaning it’s obligated to live there)

- Facultative Wet (FACW)- prefers wetlands, but can tolerate some damper uplands

- Facultative (FAC)- can grow in both wetland and uplands

- Facultative Upland (FACU) – prefers uplands, but can tolerate some dampness or flooding

- Upland (UPL)- can only survive in dry conditions, called uplands because areas high up away from water tend to stay drier

You can find lists of plants and their classification through the US Army Corps of Engineers, to help select what species might do well in a wetland near you.

Many wetlands are invisible to people who live nearby – some less obvious types like wet meadows may just seem like muddy spots in the garden. This puts them at additional risk of destruction and attempts to drain, pave, or channel water away from the area. Unfortunately this usually doesn’t work. Most converted wetlands are just made inferior – left with soil that never quite grows anything well, buildings that constantly flood, and issues with drought and flood in surrounding areas.

Tall trees to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Oak+, Hickory+, Walnut+,

- Fruit – American Persimmon+

Small trees to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Chestnut*

- Fruit – Hackberry, Apple*+ / Crabapple (Malus), Plum*+, wild plum+ / wild cherry% (prunus)

Shrubs to plant or protect:

- Nuts – Hazelnut+

- Fruit – Raspberries / Blackberries (Rubus), Blueberry / Deerberry / Huckleberry (Vaccinium), Figs*

Vines to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Hopniss / Groundnut (Apios americana)++%!

Herbs (non-woody plants) to plant or protect:

- Tubers – Katniss / Wapato / Arrowhead (Sagittaria latifolia)++%,

- Seeds – Wild Rice+, American Lotus (Nelumbo lutea)!%

Key: + great producer, ++ excellent producer, -minimally productive, ^ semi-domesticated or quasi-native, * Non native, %caution – needs processing / toxic compounds / dangerous lookalikes / common intolerances / not studied for safety, ! aggressive

Very Productive Plants

In this section we’ll go into greater detail about some of the highly productive plants highlighted in different ecosystems.

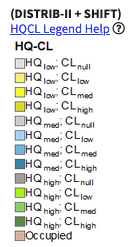

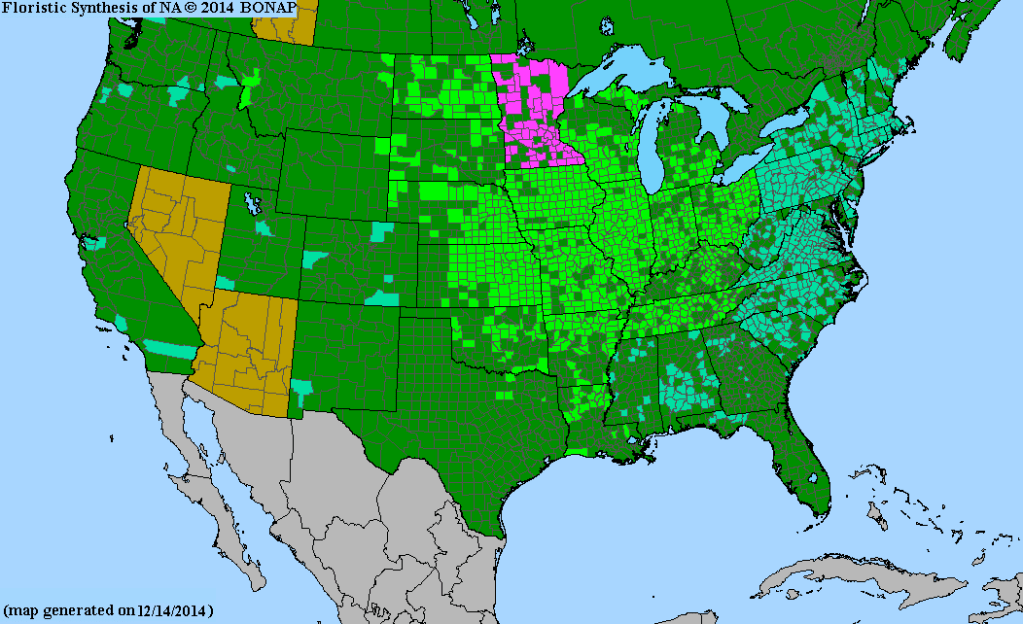

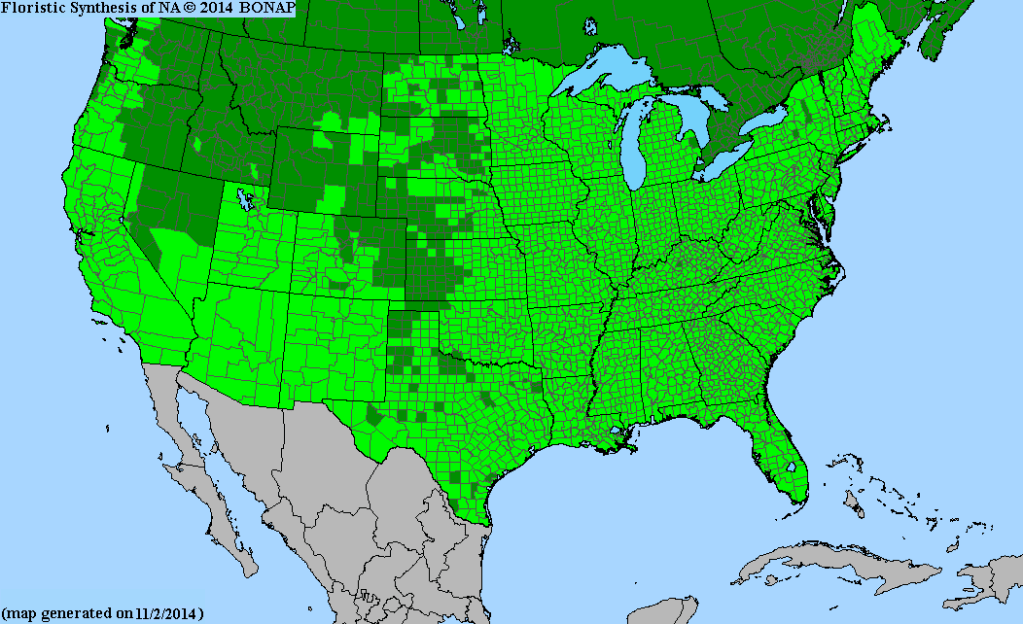

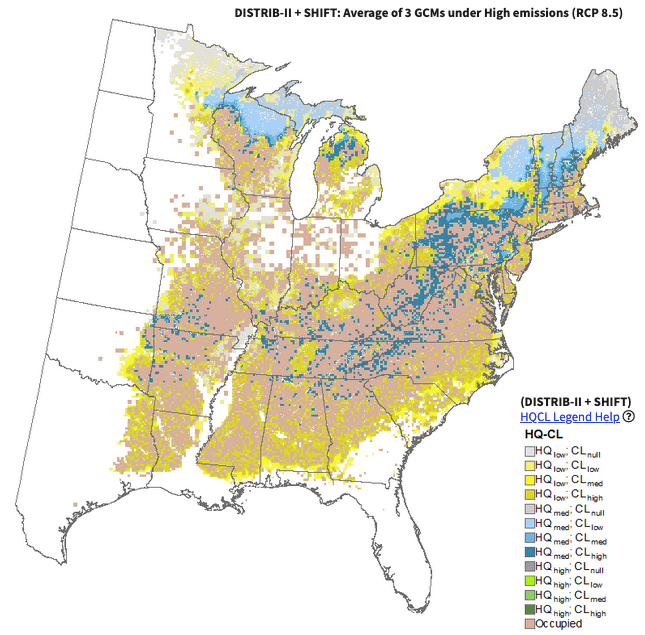

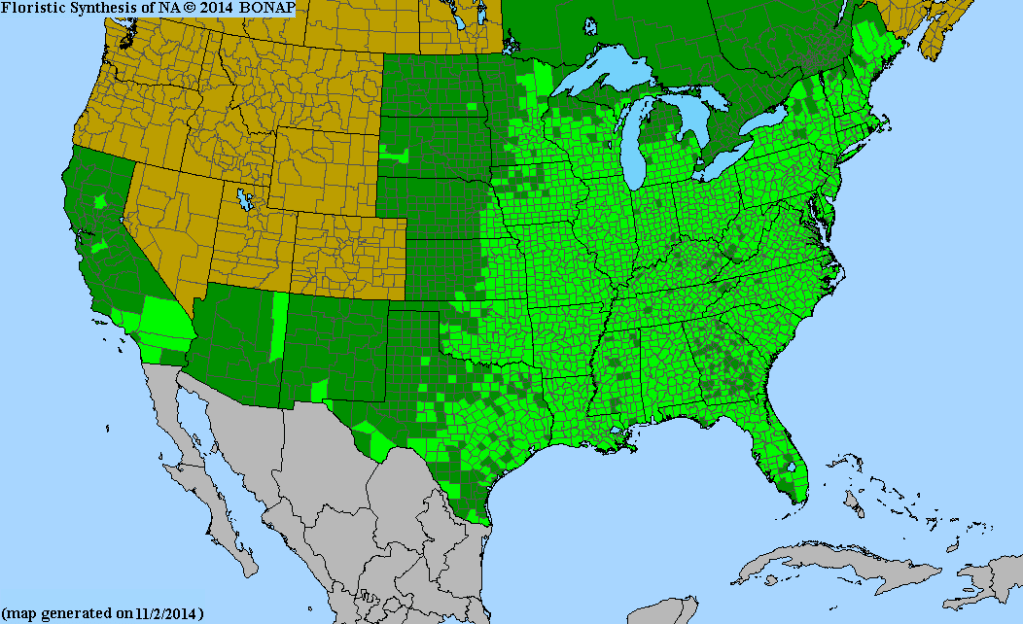

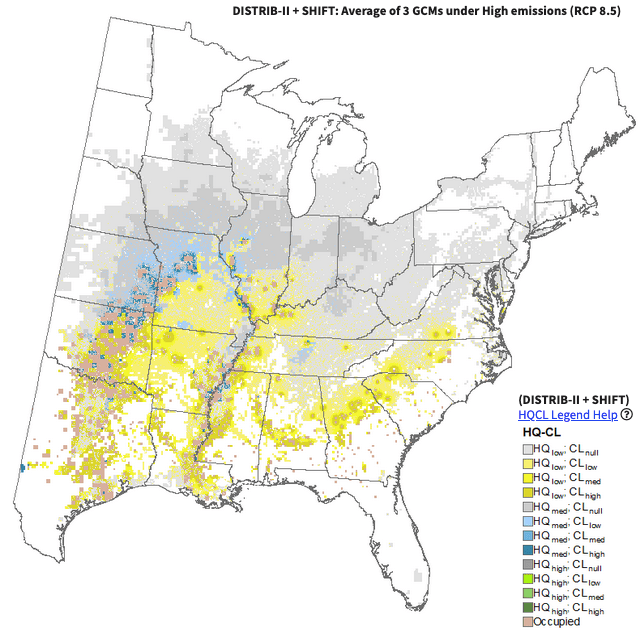

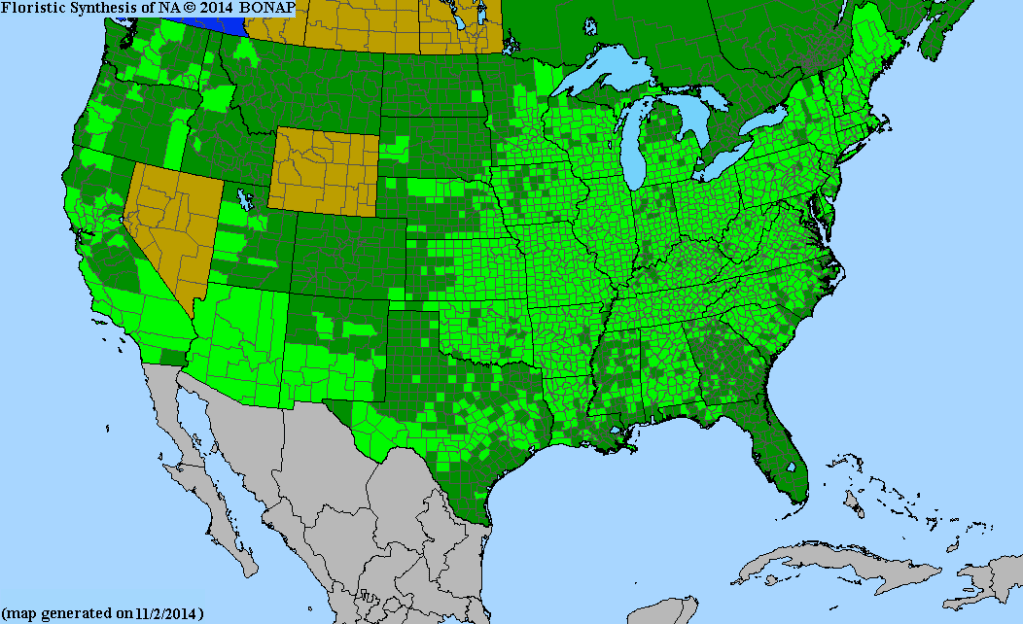

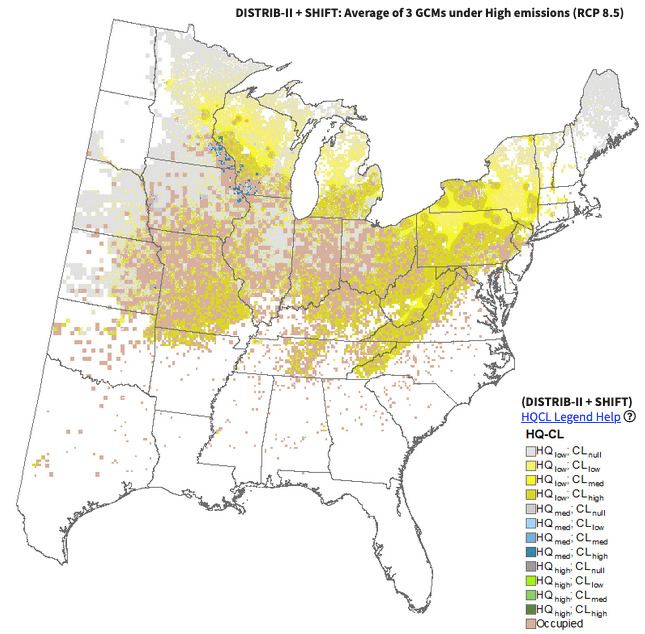

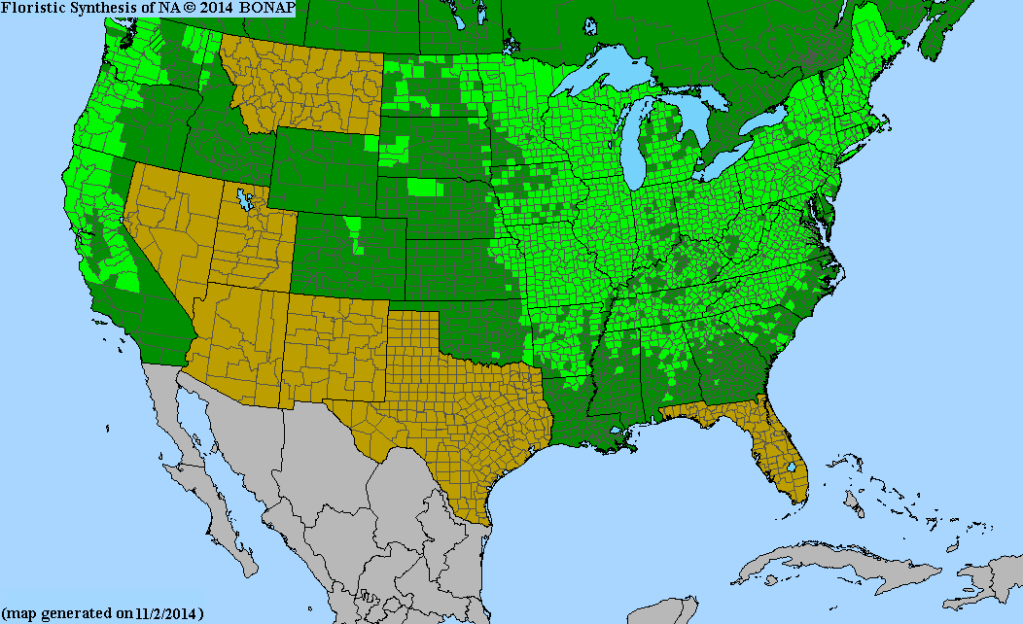

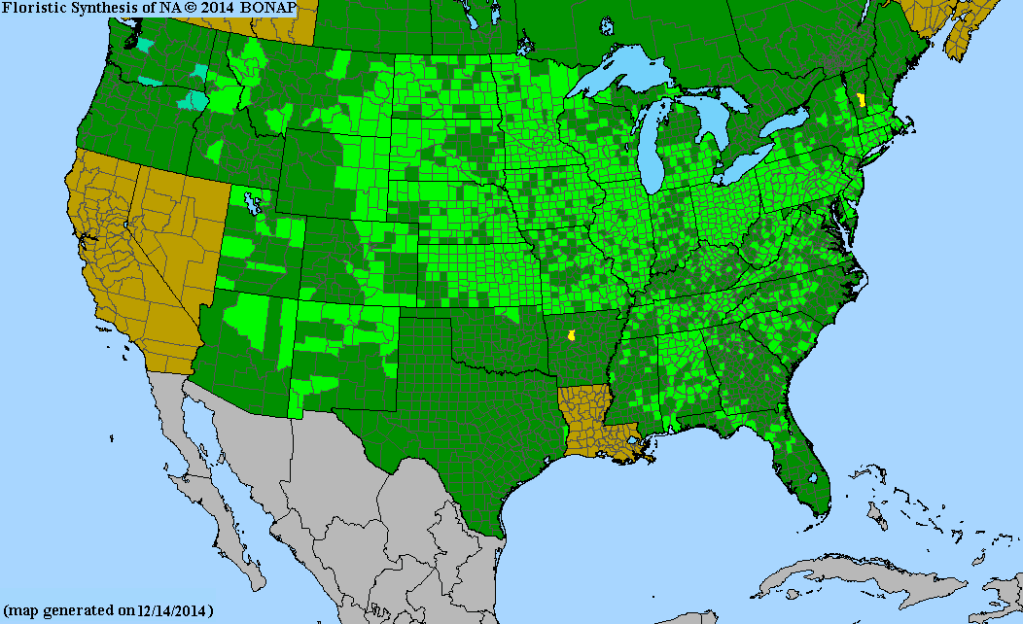

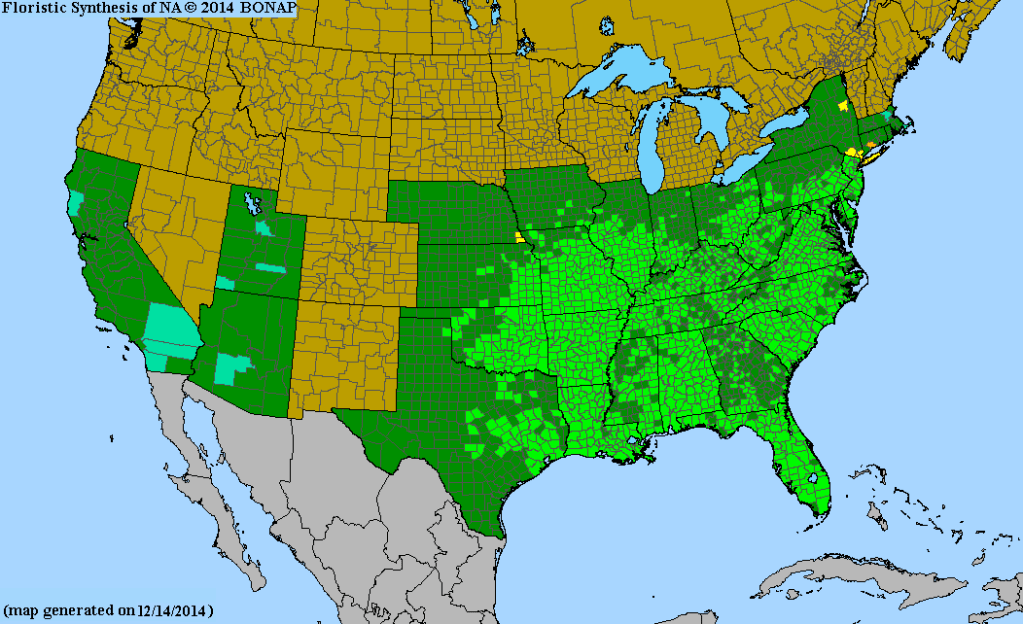

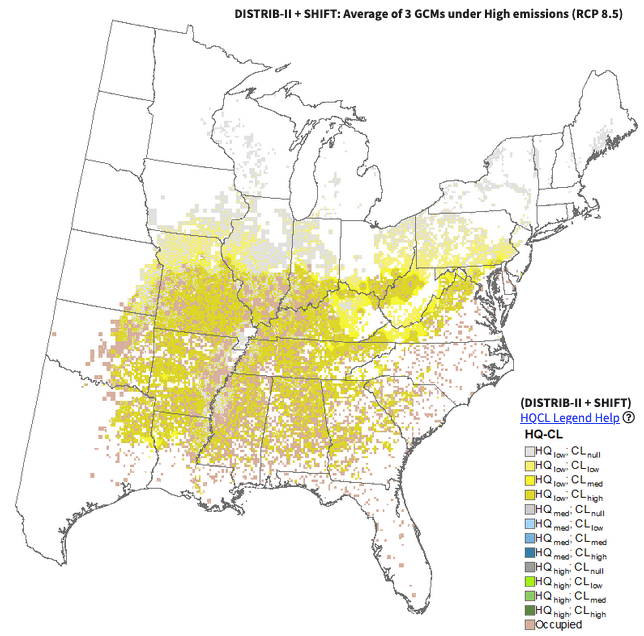

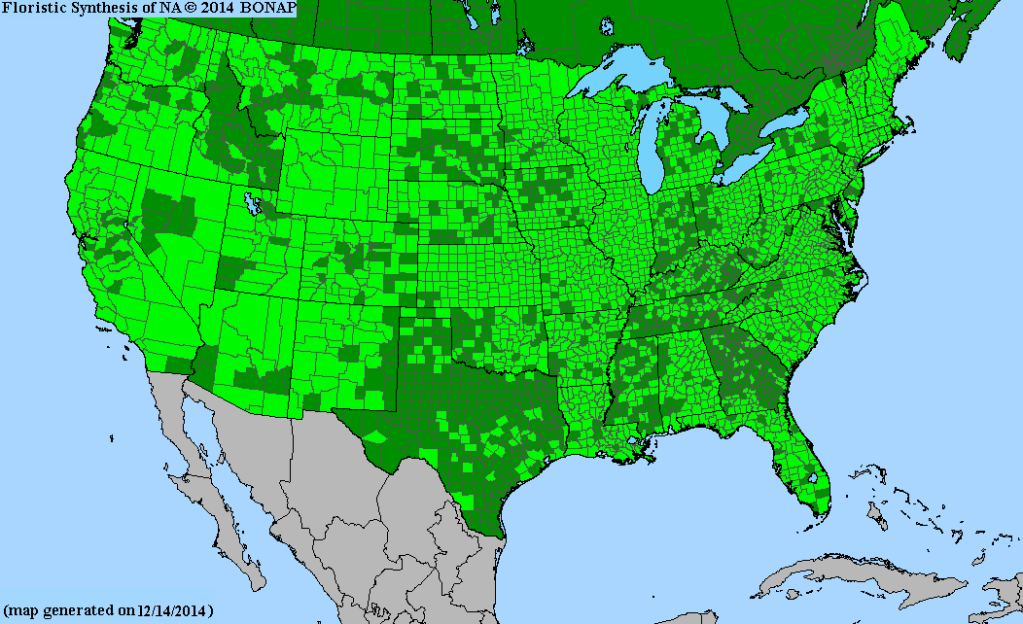

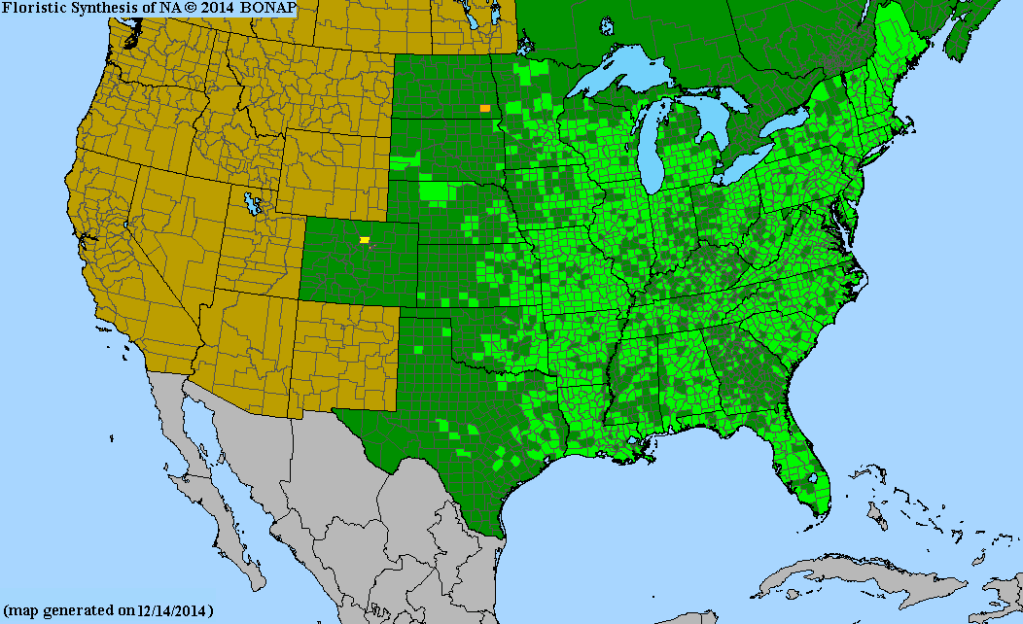

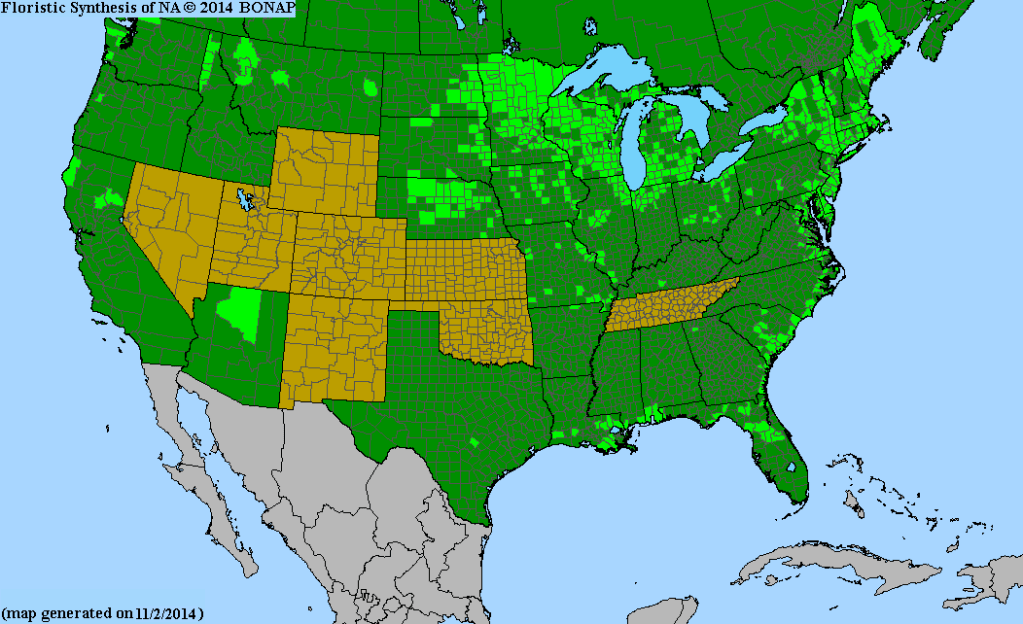

Two charts included when possible are the native plant range (through BONAP ) and the predicted future ranges under significant climate change (through the climate change tree atlas)

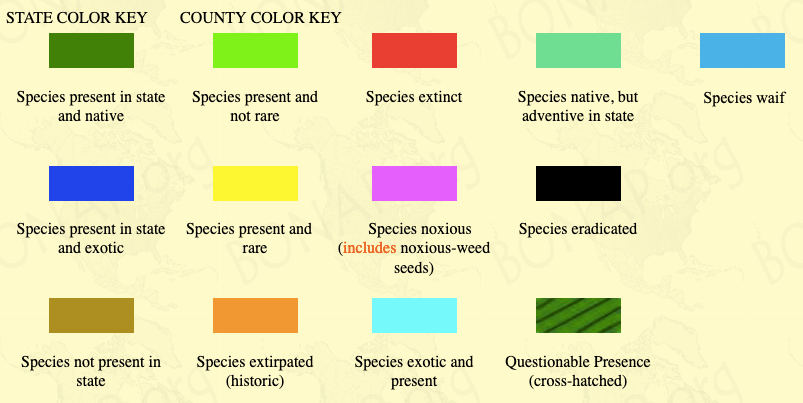

For the BONAP maps, lime green indicates counties where the plant was believed to grow prior to European Colonization (and thus are great places to grow the plants now).

The climate change tree atlas map is more difficult to read. It’s designed to show how trees may be expected to move as the climate shifts. The maps are separated into Habitat Quality (HQ) – how healthy the tree would be there, and Colonization likelihood (CL) – how likely the tree is to reach that region withing the next century.

Areas that are high quality with high likelihood of colonization can expect to see many of these trees enter the landscape. The lower the quality habitat the less suitable the trees will be, and the lower the colonization likelihood

- Pink – the tree is already there

- Green – high quality habitat

- Blue – medium quality habitat

- Yellow – low quality habitat

- Grey – the tree will not reach the habitat naturally in the next 100 years

People wanting to grow trees should look for high-quality habitat, and ideally ones where the trees may naturally move in the next century. Grey areas can clue the reader into potential population grounds for assisted migrations, or potential orchard locations.

Sunchoke (Helianthus tuberosus)

<no tree atlas model, is not a tree>

Food Type: Roots

Plant Shape: Flower

Time from planting to Harvest: Months

Harvest Frequency: Annual

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 127%

Nutrient Benefits: Starch

Landscape Types: Open Forest, Prairie

The sunchoke is a close relative of the sunflower but instead of being an annual plant that produces a lot of seeds, it sticks around for many years. A tuberous root system keeps the sunchoke alive underground during the winter months before springing back up with new growth. These tubers are the primary harvest, but the greens are also edible when cooked. Although not listed as native to the east coast, there are accounts of the European colonist Samuel Champlain in 1605 seeing what appeared to be sunchoke cultivated in what is now called Massachusetts (The plant also appearing depicted in his map).

Sunchokes are one of the few plants which appear to have productivity comparable to corn, despite requiring less labor to grow. The primary complaint with this plant is their tenacity and quick spread. In a garden context sunchokes can rapidly spread, stressing gardeners who hoped to have some place for other plants.

In wild contexts in the eastern and central USA there are varying reports of sunchoke’s aggressive properties, Minnesota has it listed as a pest plant in a few documents despite it being a native plant to their region. In Europe sunchokes are a dangerous invasive plant sweeping through landscapes. Deer and other wildlife feed on the sunchoke greens. Typically this does not kill the plant but it does slow down growth and spread.

This all highlights the duality of the sunchoke – it grows incredibly well without human aid or effort even in difficult soils, but can be so productive that it’s a nuisance or even a danger to the surrounding plants. People should be cautious planting this species – putting it only in areas where it would be ok to spread out of control, or where the plant would naturally grow in the wild.

To cultivate sunchokes, simply bury a tuber in the area you plan to grow them. Make sure the tuber is fresh and firm (unlike potatoes they get soft and rot very easily if left to dry), and choose a plant type that meets your need. For people trying to grow food, the ‘stamped’ variety is often used as it produces a lot of large tubers close to the top of the soil.

The tubers can be harvested any time, but they’re best after growing for at least an entire season, and dug up after the flowers and leaves have died in the cold season (this is when the nutrients are stored in the tubers safely for the winter). Without processing the sunchokes have a tremendous amount of fiber, so much that it can cause massive digestive upset. Traditional cooking methods eliminate this issue – put in a slow cooker for at least 12 hours and allow them to caramelize as the fiber converts to sugars. Other techniques people advocate include pickling and cooking in lemon juice, but for all recipes eat only a small amount at first to see how your body responds.

This plant is one of several potential ‘deep food storage’ species. These are food crops that can sit undisturbed until they’re needed to feed people.

Recipes:

- Slowcooker Chickpeas with Sunchokes and Chorizo

- Fully Cooked Sunchokes

- Camelia’s Lacto-Fermented Pickled Sunchokes

Oak (Quercus)

Food Type: Nuts

Plant Shape: Tall Tree

Time from planting to Harvest: Decades

Harvest Frequency: Big harvest every few years

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 30%

Nutrient Benefits: Fat, Protein

Landscape Types: Closed Forest, Open Forest, Wetlands

What we now call North America (especially in Mexico) is a major ‘center of diversity’ for Oaks. This means that the Oak tree evolved here so long ago that it’s adapted into many ecosystems through a range of different species. This means that for almost every place and habitat type, there is a suitable oak species. Blue jays are known to be tightly linked to oaks – carrying acorns across enormous distances – and may be the reason why it is has spread so far across the world.

Oaks are broadly divided into 2 groups – the red and white oaks. White oaks drop acorns earlier in the fall, which then germinate and begin growing before the winter. The red oaks meanwhile drop acorns later, which sit over winter before germinating in the spring. No matter the group, animal species depend on the oak to survive – over 400 species of butterflies and moths complete their life cycle on only this tree. This means planting or preserving an Oak tree tremendously benefits ecosystems.

All oaks produce acorns, and all acorns have tannins. These are bitter chemicals found in foods like black tea and dark leafy greens. If you pick up an acorn, crack the shell, and taste the nut inside, you will find it’s so tannic it seems inedible. Tannins naturally dissolve into water (like tea brewing), and so many cultural practices around eating acorns involve using water to draw out the biter compounds (called leeching). Cold leeching takes longer and uses cold water, and hot leeching uses simmering or boiling water. We’ll talk in a later section about some methods for leeching. White oaks tend to have fewer tannins, which also makes them more desirable to animals like squirrel and deer.

Oak trees vary in the amount of acorns they drop each year. Some years are light, and others heavy. Sometimes many trees heavily produce together – which is known as a ‘masting’ year. Traditionally a mast year would be a cause for celebration because of the abundance of food.

Recipes:

- Acorn Flour (cold leeched)

- Maple Acorn Torte (our favorite)

- Corn Grits with Acorn Flour

Hickory + Pecan (Carya)

Food Type: Nuts

Plant Shape: Tall Tree

Time from planting to Harvest: Decades

Harvest Frequency: Big harvest every few years

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 14%

Nutrient Benefits: Fat, Protein

Landscape Types: Closed Forest, Open Forest, Wetlands

Most well known by the pecan’s available in stores, the hickory family is a large tree that produces tasty nuts. The wild hickory (not pecan) is considered by some to the best tasting nuts in the world. The taste and use varies by tree – the bitternut being most useful as an oil (the nut flesh being too bitter to eat directly), shellbark as the largest and sweetest, shagbarks the most easy to crack, and so forth.

Almost everyone in the eastern half of north america (and some along the pacific coast) can find a hickory tree in their area. The only commercial nut tree in the carya family is the Pecan, which is grown in orchards through the south and is native to the Mississippi valley regions.

Like Oaks, hickories are a masting tree – their productivity varies, with some years seeing few to no nuts, and others seeing heavy production (sometimes seemingly synchronized between trees). Among the most favored of nuts by squirrels, hickories are best harvested in wide open areas where the trees can produce heavily, and squirrels are too scared to visit.

When ripe hickory nuts should fall naturally from the tree, and will drop when the branches are shaken. In ripe good nuts the hulls pop off easily into sections revealing the nut underneath. These nuts should be dried for a while before consuming for best flavor, but are safe to eat immediately.

Among the Cherokee people, Kanuchi is a traditional food made of smashed hickory nuts boiled into a rich milk, often with a starch like rice or grits. This is one of the best ways to enjoy hickory nuts. In our household we pass the milk through a blender and add maple syrup for a comforting winter drink similar to milky hot chocolate or warm horchata.

Groups such as the Northern Nut Growers Association have been developing new hybrids and varieties of hickory, which members have been growing and putting out for sale. These types are selected for characteristics such as cold tolerance, shell thickness (thinner is better), sweetness, and size of nut.

Recipes:

- Kanuchi (Cherokee recipe for hickory nut milk porridge)

- Hickory Nut Milk Rice Pudding

- Any recipe that calls for Pecans works perfectly for other hickory species

Walnut + Butternut (Juglans)

Food Type: Nuts

Plant Shape: Tall Tree

Time from planting to Harvest: Decades

Harvest Frequency: Usually every other year

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 18%

Nutrient Benefits: Fat, Protein

Landscape Types: Closed Forest, Open Forest, Wetlands

The walnuts available in grocery stores are different than the ones that grow wild on this continent. The widely sold Persian / English walnut (both refer to the same tree – Juglans regia) has a mild tasting nut covered by a shell that’s fairly thin for its family. There are a few different wild walnut species in North America. The eastern species most prevalent are Black Walnut and Butternut.

The Butternut (Juglans cinerea) used to be very very common. Many places and foods are named after the tree (including butternut squash) but the disease Butternut Canker has killed 90% of the wild population. The canker was introduced by the import and planting of Japanese walnuts in the early 1900’s, who carry the disease but can survive its infection. Unfortunately this tree was among the most desired of nut trees, with fast growth, thin shells, and delicious flavor. Many hope the tree will develop resistance and return to the landscape over the decades and centuries.

The Black Walnut (Juglans nigra) has not been set back by canker at all. The tree is practically a weed in some areas – annoying people with the nuts and dark staining rinds covering the ground in fall. It’s typically seen in damp soils along riverbanks, but they also thrive in yards, valleys, and more moist woods.

Unlike the hickory the black walnut is covered by a thick juicy rind – not unlike a thick orange peel – that must be removed to expose the nuts. Methods to do this include hand removal, stomping, and even driving over the nuts. The chemicals in the peel are a powerful dye that will stain clothes and light skin to a dark brown. Some people use this trait to make DIY clothing coloring for a light brown. After hull removal the process continues in cleaning and drying (called ‘curing’). Some folks have developed different strategies to process and clean the nuts (including forager chef’s complete guide) though it remains a messy business. Hammon’s walnuts is one of the few companies that purchases wild nuts to resell them – they do all of the cleaning through machinery at processing facilities. People bring the unprocessed walnuts to central locations where they’re purchased by the pound.

The shells of the Black Walnut are among the hardest in the world. A hand nutcracker simply will not work. Cracking is typically done with a hammer or specialized equipment. You can usually track down walnut trees in fall just by the sound of squirrels and chipmunks chewing through the thick nuts with their hard teeth – it sounds like metal coins being rubbed together – animals without those strong rodent teeth don’t stand a chance of prying one open (unlike chestnuts, hazelnuts, pecans, and acorns, which all are important food sources to numerous animals).

The high fat and protein content makes squirrels willing to carry the huge nuts far away from the parent tree and bury them for later eating. Usually these are dug up and eaten on central perches where predators are easily spotted. Near walnut trees you’ll almost always see a spot with a pile of nut rinds and shell pieces where a squirrel eats their meals.

Black Walnuts have a unique flavor that’s tough to describe. Depending on who you ask it’s fruity, cheesy, or gamey. This versatility makes it work in both savory and sweet dishes – but it requires that people get used to the flavor and learn to enjoy it. When introducing the black walnut to new folks we often describe it as ‘controversial’ – that usually makes the tasting a fun lively conversation where everyone chooses sides (instead of shutting down with the challenge of a new flavor).

Notable the Walnut is also a very valuable tree for its wood. People often plant Black Walnuts not for the nuts at all but as part of a timber farm. This means that people planting walnuts for the food can also rely on the mature trees as an emergency cash source.

Recipes:

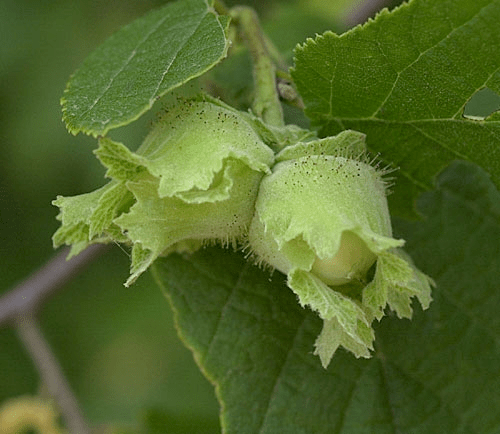

Hazelnut (Corylus)

Food Type: Nuts

Plant Shape: Shrub

Time from planting to Harvest: 5-10 Years

Harvest Frequency: Annual

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 26%

Nutrient Benefits: Fat, Protein

Landscape Types: Open Forest, Wetlands

Hazels are a highly productive nut shrub found across the temperate areas of the northern hemisphere. That includes native species in China, Turkey, Spain, Ireland, Denmark, and both the East and West of North America (but not the western mountains or open prairies). Aside from the actual nuts they produced, hazels played a critical role in the lifestyles of European peoples across several key domains.

Firstly, hazels formed living fences in the form of hedges – which are quite unlike the hedges in our gardens today. Shrubs like hazel were grown and then the stem cut almost all the way through so that it could be laid flat. This then led to a shrub or tree that grew naturally into a walled shape. This process (known as hedge laying) is a skilled task that very few people still know how to do – there are volunteer organizations that help to maintain and restore the remaining hedges in England. These hedges mimic naturally occurring shrub systems known as thickets, and are associated with improved biodiversity – with tack-on benefits to crops with the improved pollination. The berries and nuts of these living fences were also minor sources of food especially on the edges of the seasons. Though less commonly used in our region, hedges served an important role as livestock barriers in North America prior to the invention of barbed wire (especially the thorny osage orange).

The tendency of hazels to regrow new twigs stumps when cut to the ground led to their other use as a form of sustainable wood harvest known as coppicing. In areas managed by coppicing, about once a decade a stump covered in new growth (known as a coppice stool) would be cut back to harvest all the twigs and limbs. Typically an area would have many stools in different stages of regrowth such that there was always some wood to harvest every year. Species managed by coppicing live much longer than their free growing counterparts, with stools being harvested again and again for hundreds of years.

Hazelnuts themselves are excellent sources of food. So excellent in fact that wildlife seem to prefer them over almost anything else, including crops like corn. Professional growers recommend harvesting the nuts early and ripening them indoors to help reduce the amount loss to frantic animals. This means harvesting hazelnuts in the wild can prove really difficult – you need to know exactly where and when to collect the nuts, and check them often. If you arrive too late, the nuts will be gone.

Plant breeders have produced many different cultivars of hazels for nut production, but a disease called the eastern filbert blight have put many of these varieties in danger. The blight is native to Eastern North America, and the European species do not have any resistance to the disease. Cultivars are often in danger of the blight because European species are commonly part of their breeding mixes. However, native hazelnuts in the east aren’t killed by the disease. Groups like Rutgers University have been involved in trying to breed a high producing hazelnut using the immunity found in the native species. Despite the difficulty of the blight Hazels remain a popular choice for nut orchards – because unlike other nuts in the USA, hazels are a shrub and thus reach maturity and begin producing very quickly.

American Plum (Prunus americana)

Food Type: Fruit

Plant Shape: Small Tree

Time from planting to Harvest: 5-10 Years

Harvest Frequency: Every other year

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 43%

Nutrient Benefits: Carbohydrates

Landscape Types: Open Forest, Wetlands

Persimmon (Diospyros virginiana)

Food Type: Fruit

Plant Shape: Tall Tree

Time from planting to Harvest: Around a decade

Harvest Frequency: Every Year

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 18%

Nutrient Benefits: Carbohydrates

Landscape Types: Closest Forest, Open Forest, Wetlands

Cattail (Typha)

Food Type: Roots

Plant Shape: Grass

Time from planting to Harvest: Unknown

Harvest Frequency: Unknown

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 64%

Nutrient Benefits: Carbohydrates

Landscape Types: Wetlands

Hopniss (Apios americana)

Food Type: Roots

Plant Shape: Vine

Time from planting to Harvest: Unknown

Harvest Frequency: Unknown

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 56%

Nutrient Benefits: Carbohydrates, Protein

Landscape Types: Wetlands, Open Forest, Prairie

Honorable Mentions

Manoomin / Wild Rice (Zizania)

Food Type: Seeds

Plant Shape: Grass

Time from planting to Harvest: Months

Harvest Frequency: Annual

Harvest calories per area compared to corn: 5%

Nutrient Benefits: Carbohydrates,

Landscape Types: Wetlands

Reason for honorable mention: Easy to harvest a lot very quickly

Leave a comment