Sometimes we can’t buy fresh food at the grocery store. That can be due to money, location, housing status, or times of conflict. People throughout history have lived through such moments, and they kept food on the table by harvesting wild plants.

Unfortunately many of us have lost touch with wild food traditions our ancestors used, so we don’t know which plants are safe, nutritious, and delicious.

This guide is intended to help people in these circumstances.

The food plants we include are:

- Safe – no poisonous lookalikes or complicated processing required

- Common – you don’t have to travel far to find them

- Familiar – tastes like food we already eat

We also do not list any plants which are ecologically sensitive or at risk of over-harvest. These are all weedy common plants, many of which are also foreign and invasive.

To use this guide, read through our guidelines section to make sure you understand how to reduce risks when eating wild foods.

Guidelines:

There are two main concerns when foraging for wild foods:

- Plant safety – picking the correct plant, and making sure it won’t hurt you

- Environmental safety – avoiding local risks pollution which can make you sick

Foragers need to make sure they are considering both of these when collecting wild foods.

Plant Safety

Most plants are safe to eat. Only a few taste good. Only a few can make you sick. Even fewer can kill you, but there may be no antidote to save you.

Because of this it’s important to always know with 100% certainty the plant you are picking. Don’t rely on memorizing poison plants, checking for a bitter flavor, or any other popular tricks to save time. These may work sometimes, but eventually they will fail you and you will get poisoned.

We still want you to eat wild foods, and we have provided a few things to make this as safe as possible:

- For each plant we have provided 3 identification guides from independent reputable sources.

- it’s recommended to cross-reference multiple sources to make sure you didn’t misidentify the plant. We include multiple sources for you to check.

- Following 1 guide will likely be enough for the specific plants we included, but we recommend following all 3 to be safest.

- We have not included any plants which have close deadly lookalikes

- Do your best to follow the identification guides as closely as possible, if you don’t do this step, you are not protected from poison plants.

- Know the identity of every single plant you put in your mouth. Don’t rely on checking a few plants in a pile, or returning to the same spot you harvested before and expecting the same plant to be there.

Each plant also has its own properties that can still be risky for certain people. That’s why pregnant people, those with heart conditions, and babies, are told to not eat certain foods. We did our best to not list any plants that we know are unsafe to the general population – all of these could be sold in the grocery store. But that means you need to still be careful about your particular health like you would with any store bought food.

The easiest way to find this information is to look on google, or to talk to a doctor. Try to find reputable sources. Unfortunately we can’t provide simple instructions because this is so specific to each person and each plant.

Consider your health and what risks you are willing to take, and make decisions you feel comfortable with.

A note about less dangerous chemicals

Like we said above, everyone should do their own research to find out if a plant is safe for them. However, there are a few chemicals we know about that are common in plants, and have effects on the human body. We decided to include these plants in the guide because based on the data we have available, the amount of chemicals present don’t pose a risk to the general public. But because researchers have not studied these plants extensively, we don’t know with 100% certainty how much you will absorb when eating them.

We wanted to include a note on these chemicals for transparency, and to help you make the best choices for yourself. All plants listed in the guide will include a note if these chemicals are known to be present in significant quantities.

Oxalates

These are bitter-tasting molecules that occur naturally in foods like leafy greens, tea, and citrus fruits. They can reduce your ability to absorb calcium, and are associated with increased risk of kidney stones. Cooking in water and then not consuming the cook water (so boiling and draining, not cooking in stews) massively reduces the amount of oxalates, because oxalates get absorbed into water easily.

If you have a health condition sensitive to oxalates (such as kidney issues or osteoporosis), it’s worth cooking high-oxalate foods boiled or avoiding them entirely.

Thujone

An aromatic herbal-smelling neurotransmitter naturally produced by certain plants – very common in the cedar and wormwood family – often used to add herbal flavors to drinks and foods. This molecule operates in an opposite way to alcohol, and can have certain systemic effects on the brain and body. Traditionally it’s a component in absinthe.

Only minuscule amounts of thujone are present when plants are used as an herb or flavoring agent – well below any measurable effect on the body. For example, sage is a thujone-rich plant used often as a cooking spice.

To reduce the amount of thujone consumed, only use enough of the plant to get the nice flavor, and no more. You will probably not be interested in trying anyway – imagine eating a salad of just sage leaves, it would taste way too strong.

Because of the nervous system effects, it’s not recommended that people who have epilepsy or who are pregnant consume large amounts of thujone. If you are in this group you may want to avoid using thujone rich plants.

High Nutrient Density

Some healthy nutrients in foods can be present in very high amounts. If eaten in very high amounts, or over an extended period of time, these foods can lead to potential health effects.

Some vitamins and minerals are water soluble, which means that if you eat too much, your body will eliminate them when you pee. These include vitamin C, and the B vitamins. It’s almost impossible to suffer health effects from eating high amounts of water soluble nutrients.

Other vitamins are carried in oils, which is known as being fat soluble. These are much harder for humans to process and eliminate because they are stored in our body fat. Vitamins A, E, and K are all fat soluble. Of these, Vitamin A is the most common cause of illness and death when eaten in high amounts – and are the reason why vitamin pills have a child-safe lock on the bottle.

There are two ways to suffer from vitamin A toxicity – one is from eating a little bit too much every day for weeks or months (called chronic toxicity), and the other is eating an extremely high amount at once (called acute toxicity). It’s extremely difficult to have acute toxicity from food – normally it comes from taking too many vitamin pills. We do not include any foods which would cause vitamin A toxicity if eaten in reasonable normal amounts (~1 cup with every meal), but some can cause chronic toxicity if eaten with every meal for weeks at a time.

We recommend varying your diet and eating different vegetables throughout the week. This will both reduce your risk of chronic toxicity and also make your food more enjoyable. For those who are eating a narrow set of foods, or are at risk of vitamin toxicity (such as young children), you may want to be aware of the amount of high-nutrient foods you eat. All foods which contain 100% or more of daily recommended vitamin A in 1 cup, we mark as high in vitamin A.

Fiber is a healthy part of our diet, helping us to move food through our bodies, maintain digestive system health, feel full, and keep our blood sugars steady. If we aren’t used to eating fiber, eating a lot of it can cause bloating and constipation. We can develop our tolerance to fiber by slowly increasing the amounts we eat.

Those unaccustomed to a high fiber diet should be careful to increase fiber slowly. This is especially a concern for people struggling with food insecurity such as unhoused people, because processed foods tend to be very low in fiber. Including too much fiber too quickly can be very uncomfortable. All foods which contain 25% or more of daily recommended fiber in 1 cup, we mark as high in fiber.

Environmental Safety

Plants can collect and absorb dangerous contamination from where they grow. The specifics around risk and foraging in north america haven’t been seriously studied, so we don’t fully understand the safety.

What we do know is that some things are safer than others. These are the major factors to consider when thinking about risks and foraging:

Soil contamination – such as chemicals or heavy metals. Urban and roadside areas are often at risk of soil contamination. Different plants, and different parts of plants, collect pollution differently.

- To be safe, avoid: Former industrial areas, landfills, areas along busy roads, and waterways.

- Protect the most: People under 20 and people who can get pregnant – these are usually the most risky for babies and young people, and the least for adults.

- Harm reduction: Berries and nuts store the least amount of toxins, roots store the most. Eating berries and nuts are often safe even in contaminated areas.

Fecal contamination – typically this is from dogs. Fecal contamination can be as minor as giving you diarrhea, to as bad as getting infection that damages all of your organs.

- To be safe, avoid: Eating uncooked plants – cooking destroys dangerous pathogens, and picking plants along routes where many dogs and animals visit.

- Protect the most: People without access to medical care, people with weaker immune systems like babies and the elderly.

- Harm reduction: If you pick plants from high in the air, they are much less likely to have contaminants on them. You can also try to pick from areas where few animals or dogs visit.

Air contamination – smoke and car exhaust can cover plants and leave a harmful residue of heavy metals like lead as well as other chemicals. This can also be true of grocery store foods – which is why they recommend rinsing fruits and vegetables before eating.

- To be safe, avoid: Eating plants without rinsing them off in water.

- Protect the most: People under 20 and people who can get pregnant – this is usually the most risky for babies and young people, and the least for adults.

- Harm reduction: Picking away from busy areas reduces the amount of contaminants that could be on plants.

We arranged this guide to help you stay safe by not listing anything that puts you at high risk. Specifically we did not include anything that:

- Is harvested near water, to avoid risks of soil contamination.

- Cannot be cooked or collected from high up – to avoid risk of fecal contamination.

- Cannot be washed, to avoid environmental contamination.

However, many foods not listed here are still safe, delicious, and worth the effort, as long as you evaluate your local risks and be mindful of what you eat. We provided a list of good foraging books and online resources at the end of this document so that you can learn more and make informed decisions.

Wild Greens

Lambsquarters

Chenopodium album

Season: Summer

Similar Foods: Spinach, Collard Greens

Vitamins & Minerals: A, B1, Calcium, Iron, Magnesium

Warnings: High in Vitamin A

Source: University of Rochester Medical Center

Description

Lambsquarters is a wild relative of Quinoa and Amaranth. This plant and its close cousins are traditionally eaten as a cooked green in Mexico, Nepal and India. Archeologists have discovered that Native Americans and the Vikings both used the seeds as an edible grain.

This plant is common and grows everywhere – both in gardens, as well as along sidewalks and edges of lawns.

Harvest + Storage

The best parts to eat are the leaves (which always stay soft), and the very top of the plant where it is still soft – the main stem gets chewy and tough as it gets older.

After harvesting the greens, bring them home and rinse them off before putting them in a bowl of cold water. They will become more fresh and crunchy in the water. After they look fresh, dry them off and put them in a container in the fridge. You can also freeze or dry them.

Lambsquarters also have edible seeds but most people don’t harvest them – it’s annoying and doesn’t produce much food. The raw seeds form as little green balls at the tops of the plant. You can gently tap them off the plant – they will easily drop off when ripe. It is annoying to separate the seeds from the bitter green coating, but you can rub them away through a strainer with tiny holes, or between two pieces of sandpaper.

Identification

| When lambsquarters is young and edible, its leaves are roughly ovoid, or egg-shaped, tending to be somewhat four-sided or lozenge shaped, with the margins (the edge of the leaf) roughly toothed (sawtooth edges on the leaf) toward the point. These leaves are dull green with a whitish mealiness, and this white dust is much more pronounced on the underside than on the upper surface. Before cooking, lambs-quarters leaves are unwettable, that is, water either runs off them leaving them dry, or else it stands in drops without wetting the leaf surface. When boiled they lose this quality. |

| Branchy annual (lives only 1 year) herb (green and flexible like a vegetable, not woody like a tree), the limbs ascending (starting parallel but then going upward). Stems erect (straight up), 1-10′ (30-30cm) tall and up to 1.2″ (3cm) thick, solid hairless, ridged, mostly green but sometimes red, especially near the nodes (place where leaves and branches connect to stem) . Leaves alternate (one leaf on one side, then the other leaf on the other side later on – not in pairs. See image in glossary), 1-4″ (2.5-10cm) long, moderately thick and semi-succulant (full of water like a cactus, instead of dry like an oak leaf), lanceolate (looks like the head of a spear – like an oval that comes to a point, wider at the base. See image in glossary) to triangular or diamond shaped, sometimes broad and resembling the namesake ‘goose’s foot’, the base broadly angled with straight edges, the blade (the leaf) flat. Surface dull, bluish green above, but greyish green below with a powdery coating that is often very prominent, especially on the tips of vigorously growing shoots. Midvein (vein in the center of the leaf) and secondary veins (the smaller veins that come off the midvein) are slightly depressed above, veinlets (smallest veins towards the edge of the leaf) mostly flat and obscure. Margins (the edge of the leaf) may be entire (no teeth or lobes like the maple leaf on the canadian flag- flat and smooth like a spinach leaf) (especially on narrow leaves) wavy, or coarsely and irregularly toothed (sawtooth edges on the leaf) with large blunt teeth- but teeth usually appear only distal (tip of leaf) to the widest point. Petioles (the stalk that connects the leaf to the stem, comes off with the leaf when you pick it) 40-80% of the blade length, roundish with a small groove on top. Infloresence (flowers) dense and often very large branching clusters at the ends of stems and in upper leaf axils (the main stem everything connects to), spike-like, with a sessile (no separate stem, attactches directly to the main plant stem) flowers. Flowers tiny and unshowy (not flashy – more like brocolli than a tulip). Seeds dark, roundish, semi-flat, 1-1.5mm across, enclosed in a granular (covered in dots like a massage ball) usually adhering (sticks and doesn’t like to come off) seed coat (the protective skin of the seed – like a sunflower seed after you take off the shell, or the skin of black beans). |

Stinging Nettle

Urtica dioca

Season: Spring

Similar Foods: Spinach, Collard Greens

Vitamins & Minerals: A, B6, Calcium, Iron

Warnings: N/a

Description

Stinging nettle is a traditional spring vegetable – one that people ate as their winter food stores ran out. Nettles are covered in stinging hairs that make most animals avoid it. This sting is not like poison ivy or hot pepper – there’s no irritating oil and it cannot be spread by clothes. There are tiny needles all over the plant that work a lot like bee stingers, injecting tiny amounts of irritating chemical under the skin.

When the plant is cooked, dried, frozen, or crushed, the needles become broken and can no longer sting. You can easily protect your hands by covering them with a sweatshirt sleeve or cloth gloves (latex gloves won’t work).

Nettles start growing in the late winter or early spring. They begin as tiny short bunches of green leaves, which can grow as tall as a person by the end of fall.

Harvest + Storage

The top of the plant is the most tender and sweet, but the entire plant is edible. In the early spring when nettles first emerge, you can take a pair of scissors and snip off the tops of the plants into a cloth bag. You can continue doing this throughout the year but the plant will become more bitter and chewy over time – leaves towards the top of the plant will be more palatable.

Because these plants have energy-storing roots that survive winter, they can grow back even after being cut back. A patch of nettles will become weak if they are harvested too many times in a single year, but they are very difficult to kill. A few harvests a year will keep the plants healthy and cause no harm – especially if you only cut the tops of the plants and leave behind leaves and stems at the bottom.

The leaves can be dried in bundles. Tie the stems together into a bunch and hang them upside down someplace indoors. When they become crunchy they no longer sting, and can be crushed into a container like a glass jar where they can be stored for a year or two (if there is any moisture in the jar they will rot – make sure the leaves and container are extremely dry)

You can also freeze nettles and they’ll store well. They can be frozen raw or after being cooked. Frozen nettles can no longer sting.

Identification

| An unbranched weed one to several feet high, small inconspicuous flowers, fine bristly hairs all over the stem, leafstalks and underside of leaves. Very obvious. The bristles sting greatly when gently touched. |

| Perennial (lives more than one year) herb (green and flexible like a vegetable, not woody like a tree) forming colonies, by thin, pale, rhizomes (roots that connect plants together, usually growing horizontally instead of up and down). Above-ground parts are armed with stinging, needle-like hairs – more so in full sun or on richer soil. The plant has a musky odor, especially when young. Stems not clumped, erect, 3-10’ tall with blunt corners and 4 deep narrow grooves, mostly unbranched unless the plants are cut or toppled. (Branches are minor if present, sometimes greatly reducing leaves.) Leaves numerous, paired, evenly-spaced, nearly uniform in size, 3-6” long, broadly ovate (egg-shaped) or lanceolate (spear shaped), dark green and rough, the tips long-pointed to blunt. (The first leaves of shoots are broader and blunter than older leaves. Both surfaces have erect (straight up), needle-like stinging hairs, but these are more prominent on major veins and are smaller and sparser above. Midvein (vein in the center of the leaf) deeply depressed above and protruding below. There are 2-6 major secondary veins from the base, plus a few more arising distally (tip of leaf) on the midvein, also deeply depressed, giving a pleated appearance. Veinlets are depressed but less so. Margins (the edge of the leaf) have large, sharp teeth, often double-toothed. Petioles (the stalk that connects the leaf to the stem, comes off with the leaf when you pick it) 40-80% of the blade length, grooved on top. Stipules (leaf-like structures where the leaf and stalk connect) are narrow and tapered, 1cm straight-edged, minutely wavy. Flowers tiny, greenish, inconspicuous, clustered along short stems hanging from leaf axils (the main stem everything connects to) from early to late summer. |

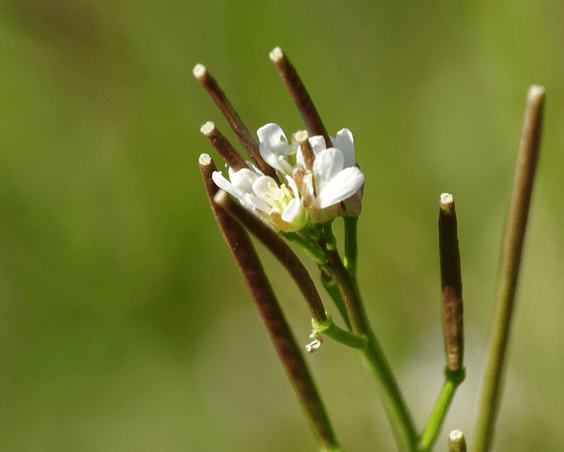

Hairy Bittercress

Cardamine hirsuta

Season: Spring / Fall

Similar Foods: Kale, Collard Greens

Vitamins & Minerals: TBD

Warnings: N/a

Hairy bittercress is a wild relative of broccoli. They’re a common garden weed that pop up in the cooler months of spring and fall. You can often find them on top of mulch, in garden beds not recently weeded, and the edges of fields.

Harvest + Storage

Bittercress can easily be pulled up in bunches, just grab the circle of leaves and pull up. The best part of the plant to eat are the leaves and young flowers. Cut off the root and any tall flowers or seeds with a pair of scissors or a knife. These bunches can then be added to dishes whole or cut into smaller pieces.

These are best eaten fresh.

Identification

TBD

Dandelion

Taraxacum officinale

Season: All year

Similar Foods: Kale, Collard Greens

Vitamins & Minerals: Calcium, Iron, B1, B2, B6, A

Warnings: N/a

Dandelions

Harvest + Storage

TBD

Identification

Chickory / Taraxacum officinale

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Purslane / Taraxacum officinale

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | Iron | High in Fiber |

Pigweed / Amaranthus retroflexus

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Wild Spices

Woodsorrel / Oxalis

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Pepperweed / Lepidium

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Spicebush / Lindera benzoin

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Onion Grass / Allium vineale

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Chives | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Garlic Mustard / Alliaria petiolata

| Season | Similar foods | Vitamins & Minerals | Warnings |

| Spring | Spinach, Collard Greens | A, B6, Calcium, Iron, | High in Fiber |

Leave a comment